Centro de Arte Juan Ismael · Puerto del Rosario, Fuerteventura

30 September – 20 November

Coded region of undeciphered clods, impregnable furrows, esoteric scarps sculpted in large flat boulders and claypits. You open your eyes. You see a book of whitish earth sealed in chests of rock. Pages of barren solitary plots which, some evenings, a humped houbara bustard crosses striding over the dust.

Coded earth. Made of tough precious stone and loose stubborn rock.

Calligraphic expanse of salty brambles which the bearded old sun of the dead has ploughed up with a yoke of obsidian.

You open your eyes: bare skinned writing. Illegible work of the gale; a toppled literary monument.

A manuscript of torn-out pages, erased and abolished by the insomniac simoom. A Zurbaran-like still-life of nothingness.

Land –or cypher– of the book.

· Francisco León ·

Some perspectives call for agreement and silence. Others encourage inquiry and leave open questions. The perspective developed by Hans Lemmen (Venlo, Holland, 1959) is among the latter. His creative complexity, which has diversified since the mid-1980s into various disciplines, is rooted essentially in drawing: the drawn line produces and releases images that seek to explore the emotional geography of the human being. The meanings of his drawings are not formed through fixed codes, as in language, but from the joins and connections that the creative process itself generates. His images are born of a tension between controlled execution and a need, pointed out by the artist himself, for the result to always surprise him. In this regard, Lemmen understands drawing as a process of birthing that struggles to find its form: the drawn line on paper offers him the possibility to break through the barrier of the everyday and light the way to the unexpected, the unsayable, and the revealing.

Hence, drawing, understood as an experience of transformation and as a place of questioning, cannot possibly be complacent towards reality. The emphatic nature of the line exists alongside an imaginary that translates the psychic dimension of the human being; it also places us in landscapes where the horizons of his native Limburg reverberate and activate strange, enigmatic, and unsettling situations. It is not, in any way, a case of hieroglyphics that are meant to be solved, but rather of scenes capable of picking out what the conscious mind is unable to recognise: mythical paths that, without obeying strict orders that could be regulated by science, we understand as essential in the construction of our societies.

For Lemmen, therefore, drawing is not a means with which to communicate certainties or specific knowledge; it is the raw material through which doubts, desires and memory are staged. We are faced with a process of reflection that takes shape through subjective experience, but in search of a possible common reason. Lemmen’s visual imaginary comes from contact with a mythical memory and sets up the possibility of questioning emotions, affections, and collective conflicts. This formulation has given rise to numerous series and working groups: it is unfurled on paper through symbolic scenes, equipped with narrativity, where closed endings are never established. Their images are therefore not placed in the realm of the story, but in a conceptually more complex one: that of myth.

Drawing, myth, and ritual

The birth of the modern subject in the West involved a transformation of temporal experience: the rate of goods production, linked to progress and technological acceleration, imposed a homogeneous and linear time. Pluralistic times—subjective, local, and individual—typical of the human, and impossible to fit into the new chronological imperialism, were left on the side lines. Lemmen’s drawings are shaped as forms of resistance to that productive and regulated time: they seek to rethink our present through the primeval, that is, outside the evolutionary framework imposed by historical and scientific accounts of Western modernity.

Omar Pascual-Castillo pointed out that Lemmen’s production generates a “mythology that defies space and time”. Indeed, his production is formulated through temporal and spatial disagreement, interwoven in the tragic aura surrounding human bonds with a primeval nature. And it is precisely in these bonds that the possibility of myth acquires a presence, never the product of a capricious invention of imagination, but inspired by man’s deep sense of fear and respect for the phenomena of the natural environment. The conceptual form of myth would therefore be the culturally primitive way of opening up to the world.

Ernst Cassirer emphasised that, in order to achieve a proper understanding of myth, one must begin by studying the ritual: the philosopher’s research showed that ritual is a deeper and more enduring element than myth, for when a human being performs a religious ritual or ceremony, he does not enter or remain in a contemplative state, but instead lives a life of emotions. Thus, the man who performs a magic ritual does not differ from the man of science who conducts an experiment in his laboratory, or from the artist who undertakes a cultural artefact. For his part, John Berger reminds us that Cro-Magnon Man was not a cave-dweller. He entered the cave to participate in certain rituals, of which we know almost nothing, although rock drawing seems to be part them.

A drawing is not important because it records what one has seen, but because of what it allows you to see. Lemmen’s drawings speak to us of many things, but also of the artist’s creative process: in his small drawings, he prepares the paper with five layers of casein on each side and then creates an abstract line that represents a horizon and that, in the end, will become the stage on which the complex spectacle of his iconography will be set. In his large drawings, the tracing of the line on paper begins with a ritual, which results in an initial mapping of emotions, “like walking on paper with paint on your feet,” the artist points out. To do this, the ritual acquires a more physical sense, through footprints of animals, plants, or even his own, as a transfer of the exterior to the interior of the work of art. In these latter pieces, the portable memory of nature is present, the haphazard traces left behind by the act of walking, the echo of the vision, as well as a hypothetical map that gives an account of the metamorphic power of the landscape.

Paths and forest clearings

In Off the Beaten Track, Martin Heidegger developed a very different notion of the path from the one formulated by Descartes in Discourse on Method, understood as a linear path of reason. The new path proposed by Heidegger is meandering, with traces, detours, movement, areas of light and shade, which speak of other presences and, also, ancient walkers. The journey that Heidegger proposes does not lead to any other place: it creates a clearing from which to think about being within a permanent mystery. Now thinking is walking and walking is thinking.

Also for Lemmen, the path travelled and the places explored are more important than the expectation of arriving at a specific point. His attitude is peculiar within the current meanderings of contemporary art, which have largely elevated the banal above the enigmatic, the eschatological above the sacred. His is, in contrast, a work that questions life as a common problem, that is woven against the grain, without conceptual rhetoric, and which explores those questions that cause certainties to tremble. His reflections translate into his way of drawing, as well as engraving, sculpting, and his installations. But beyond the chosen medium, I think that the important thing for Lemmen is to be outdoors: to develop an open-air creation, without a roof or any qualms.

His works are figurative, but imitation plays a small role, narration transgresses logic, trauma (individual or social) acquires presence, and intuition is superimposed over any canon. These characteristics lead us to understand that Lemmen comes to be defined as “a variant of the Art brut artist”: this is no longer about the unattainable “totally pure artistic operation” that Dubuffet wished to see in Art brut; but about engaging in a work that arises from the mind and that, without drifting into surreal psychic automatism, seeks to amaze the drawer himself.

Recovering aura

Walter Benjamin warned us of a before and an after in the history of images: although the work of art has always been reproducible, with the technical reproducibility typical of photography and cinema we have lost the here and now of the work, its authenticity, its aura. The philosopher emphasised “ritual” (cult value) as the foundation of authenticity in a work of art, and complained that, because of its reproducibility, cult value had been exchanged for the value of exhibition. What he did not foresee was the complex process that the image would undergo as the 20th century drew to a close: from virtual reality to surveillance technologies, there is now a new framework of hypervisibility where the task of art as a symbolic image has become complicated to unexpected extremes. Now, the condition of an image is determined by its visibility, its capacity for multiplication, and its digital circulation.

Lemmen’s perspective on the photographic image takes these aspects into account and is interested in investigating the endurance of its analogue dimension: the one that, thanks to its material condition and physical and chemical processes, is still able to reveal a tangible materiality to us. In recent years, the artist has undertaken collaborative projects, travelling to photographic archives abroad to interact with plastic processes that are ultimately processes of knowledge.

In 2017, he was invited by Roger Ballen to manipulate and alter his photographic images. Despite being thousands of miles apart —Ballen lives and works in South Africa, and Lemmen on a traditional farm in the Belgian region of Hesbaye —, they engaged in productive and extensive dialogue by way of a Cadavre exquis: Lemmen trimmed and reduced Ballen’s photographs to simple fragments in order to create new pieces, while Ballen used Lemmen’s drawings to include them in an installation that would then, in turn, be photographed. The result was Unleashed, a joint exhibition where they both explored the expressive subjectivity of the photographic image, while multiplying its symbolic possibilities. And this was achieved through narrative, expansive, and expressive images, defending the strength of the eclecticism and hybridisation contained in both imaginaries.

Unleashed can be read, at first glance at least, as an example of a certain type of postmodern work that, since the 1980s, has placed fusion, appropriation, and hybridisation at the centre of its poetics. However, Lemmen and Ballen’s proposal appealed mainly to the emergence of a new reality based on dialectical enrichment. In this sense, the project is closer to the “Diurnes” that Villers and Picasso carried out in 1953 than to the postmodernist assault on photography (based, to a large extent, on kitsch and pastiche). What unites the two projects, Diurnes and Unleashed, is the understanding of the image as a ductile matter. Photography would therefore not be a static version of things, but a living entity whose communicative possibilities overflow traditional ways of looking and seeing.

Landscape as palimpsest

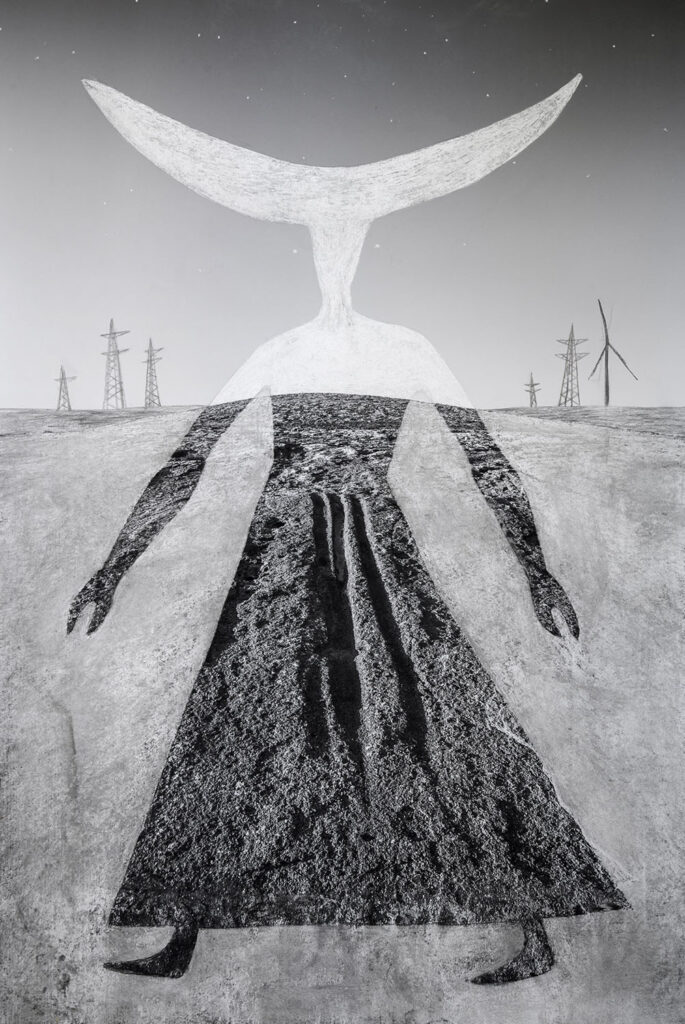

After Unleashed, Lemmen went on to develop new technical possibilities of fusing drawing and photography. His interest in the photographic archives of others lies, in the words of Didi-Huberman, in their “perforated nature”, that is, in their deliberate or unconscious censorship. This involves the search for a new technique capable of interweaving itself into the smooth skin of the photographic surface and exploring, almost literally, that same perforated nature: little by little, he will feel out different options until, finally, he decides to manually remove some of the material from the photographic print itself. Along with this scraping out, the artist’s hand draws and overlays new iconographies in charcoal.

This collection, grouped under the title Tierra Cifrada/Encrypted Ground, takes as its basis two photographic archives: on the one hand, images captured by the German photographer Thomas Mayer, especially his work around rubbish tips and abandoned houses in Ireland. But the main block of work is based on images by Spanish photographer Terek Ode, especially those documenting prehistoric structures and archaeological landscapes located around the Canary Islands. Landscape will therefore be the starting point for an archaeology of memory, myths and, above all, the concern of a human being who is struggling to find their origins.

Terra Cifrada/Encrypted Ground is located in a furtive area where photography and drawing do not clash but instead transcend one another; this is not just a formal exercise in exploration but a lucid reflection on perception, understanding and the infinite possibility of raising questions through visual composition and iconographic representation. One of the most suggestive aspects of this series is precisely related to the problem of the gaze, denying visual pleasure its specificity (photograph or drawing), and creating disquiet in the spectator, not knowing exactly what they are looking at, or rather, what their gaze is taking in.

Ultimately, the creative process generates palimpsest: the ancients used the term παλίμψηστον, which means scratched or scraped again, to refer to parchment in which an old manuscript was erased and a new one transcribed on that same medium. The practice of palimpsest is always traumatic: it inflicts a wound that makes something invisible and absent; and a new discourse forms a scar over that same wound. Tierra Cifrada/Encrypted Ground assumes this process to talk about human links to nature and, ultimately, the permeability of life and death.

Final Coda: confronting images

In the book Confronting images, Georges Didi-Huberman explains that we do not look only with our eyes, not just with our gaze. In Spanish Seeing (Ver) rhymes with Knowing (Saber), which suggests that the uncultivated eye does not really exist and that we also embrace images with words and processes of knowing. When Lemmen confronts photographic images, he assumes them as a repository of different memories and knowledge: for this reason, he is interested in creating tension in contradictory temporalities and building a visual experience outside of ordinary perception.

The skin of the photograph, scratched and peeled, begins to burn and demands new narratives: the artist introduces recognisable elements from his own environment, details of the farm where he lives in the Belgian region of Hesbaye, or the electricity pylons that surround the territory. He also draws human bodies, which are oversized in relation to the new photographic landscape they inhabit. This dislocation of scale, which erases any naturalist claim, points to one of the fundamental interests of Lemmen’s poetics, namely, the understanding of human beings as a “walking paradox”: on what basis can we claim that a more rational society is freer? Has this rationalisation of the modern world not led us down the path to disenchantment and desacralisation of the world? Do myths, philosophy, and science not operate on the same frontier?

Lévi-Strauss warned that the variety of myths, far from constituting an anarchic proliferation of stories, exhibits an air of familiarity that lays bare the deep unity of human thought. The evolutionary and progressive conception of knowledge, in which philosophy overcomes myth, and science overcomes philosophy on a scale of increasing rationality, would be an unacceptable theory. Modern science still dreams of formulating a theory that encompasses the entire universe. But myth and philosophy are not ways of thinking that science has left behind, but instead travelling companions who continue by its side: each has its own history, whose turning points and evolution are often linked, but do not necessarily coincide.

Ultimately, Lemmen views art as a de-sacralised form of myth. Hence we can understand his work as an exploration of human complexity, always through an awareness that we are not only rational animals, but also the ultimate mythical animal. For Lemmen, therefore, drawing is not a problem based on making the real present, but on transforming reality through the imaginary. His works, like ancient myths and rituals, appeal to all individuals, address both intelligence and sensitivity, claim the contest of rationality and affectivity, and activate memory and imagination.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

(1) Pascual-Castillo, O (2011). Hans Lemmen …aún terrenal [dibujos / drawings]. Centro Atlántico de Arte Moderno: Las Palmas de Gran Canaria.

(2) Cassirer, E. (1993). El Mito del Estado. México: Editorial Fondo de Cultura Económica.

(3) “La mayor parte de los animales representados en la cueva Chauvet eran feroces, pero no hay huella alguna de temor en la forma en la que están dibujados. Respeto, sí, un respeto íntimo, fraterno. Por eso todas las imágenes de los animales que se encuentran en la cueva tienen una presencia humana. Una presencia que viene revelada por el placer. Todas las criaturas aquí representadas se sienten uno con el hombre: extraña manera esta de formular algo que, sin embargo, es incontestable”. Berger, J.(2011) Sobre el dibujo. Gustavo Gili: Barcelona.

(4) Kuspit, D (2006). El fin del arte. Madrid: Akal.

(5) Benjamin, W. (1989). “La obra de arte en la época de su reproductibilidad técnica”. En Discursos Interrumpidos I. Buenos Aires: Taurus.

(6) André Villers, fotógrafo francés, cuenta con 23 años cuando conoce en 1953 a Picasso, quien le ofrece su primera cámara de fotos. Fascinados por la riqueza del lugar donde residían, la Provenza, decidieron embarcarse en un intenso proceso creativo del que surge la suite “Diurnes”, del latín “diurnus” –cotidiano–, elaborada en 1962 y editada con textos del poeta Jacques Prévert. Recluidos en el cuarto oscuro que el joven tenía en Lou Bladuc, los dos artistas producirán algo más de medio centenar de originales de los cuales seleccionaron una treintena para la edición de litografías. El porfolio, que aúna las técnicas fotográficas con las de la litografía es uno de los pocos trabajos donde Picasso utilizó la fotografía como medio de expresión. Mediante la superposición y aplicación de “découpages” –recortes de papel– con siluetas de figuras, el malagueño recreó todo un imaginario de mitología picassiana sobre los evocadores paisajes en blanco y negro capturados por la cámara de Villers.

My dogs speak

the language of stone

sniffing the deep

strata of earth

communing

with serpents

at noon they drink

from daturan drains

and on nights

of weary suns

in dreams they form a pack

and devour their master.

· Francisco León ·

I wander into the desert, naked, stooped over like a greedy monster. I flee in shame, bowed down to the ground, to open in secret the egg stranded this morning by the tide. I thought: «I’ll carry it to the temple, beyond the last beach, where no one has ever been, to the place only I know». I carry it now in my hands and feel drums of impatience beating in my chest. I am hungry, hungry with unspeakable forebodings. I cross the high solitary moorlands dragging the greenish locks of my beard. Passing by tamarisk groves peed on by imaginary goats, I wander into the desert and go down a gully. The egg is heavy, like a body with a sleeping creature inside, a fish, or a newt. Finally, I take a pointed stone and strike it furiously until it bursts, and its red and thick and sickly-sweet pulp stains my hands and lips, and my mouth welcomes it with yearning and relish, like a greedy monster—the allpowerful fruit of origin.

· Francisco León ·