… an essential and transcendent Nature that identifies us.

Carlos E. Pinto

What happens while you live¹

_Notes on the depths plumbed by Julio Blancas_.

Dalia de la Rosa

Throughout life, we do something that we don’t usually name: we create a constellation. Not with stars, but with moments. A half-spoken sentence. A smell that returns when it’s least convenient. The bright shaft of light that filters down through two branches. The roughness of a stone beneath the sole of our foot. With this minimal material—so concrete and yet so unstable—we are constructing a narrative: the story we tell ourselves to understand who we are and the story we offer to others so we can be with them.

Memory, however, is not a locked box. It does not store: it composes. It orders and disorders, emphasises, erases, illuminates once more. Experience is not left intact; it is transformed. And that transformation is not a mistake, but its way of existing. That’s why the phrase ‘what happens while you live’ has a kernel of hard truth: it points to what doesn’t fit in the inventory of major events. What happens while you live encompasses all that is not announced. That slips through. That repeats. The darkness and the cyclical return of light. Excess and moderation. The secret current that runs through the day and at the same time lays its foundations.

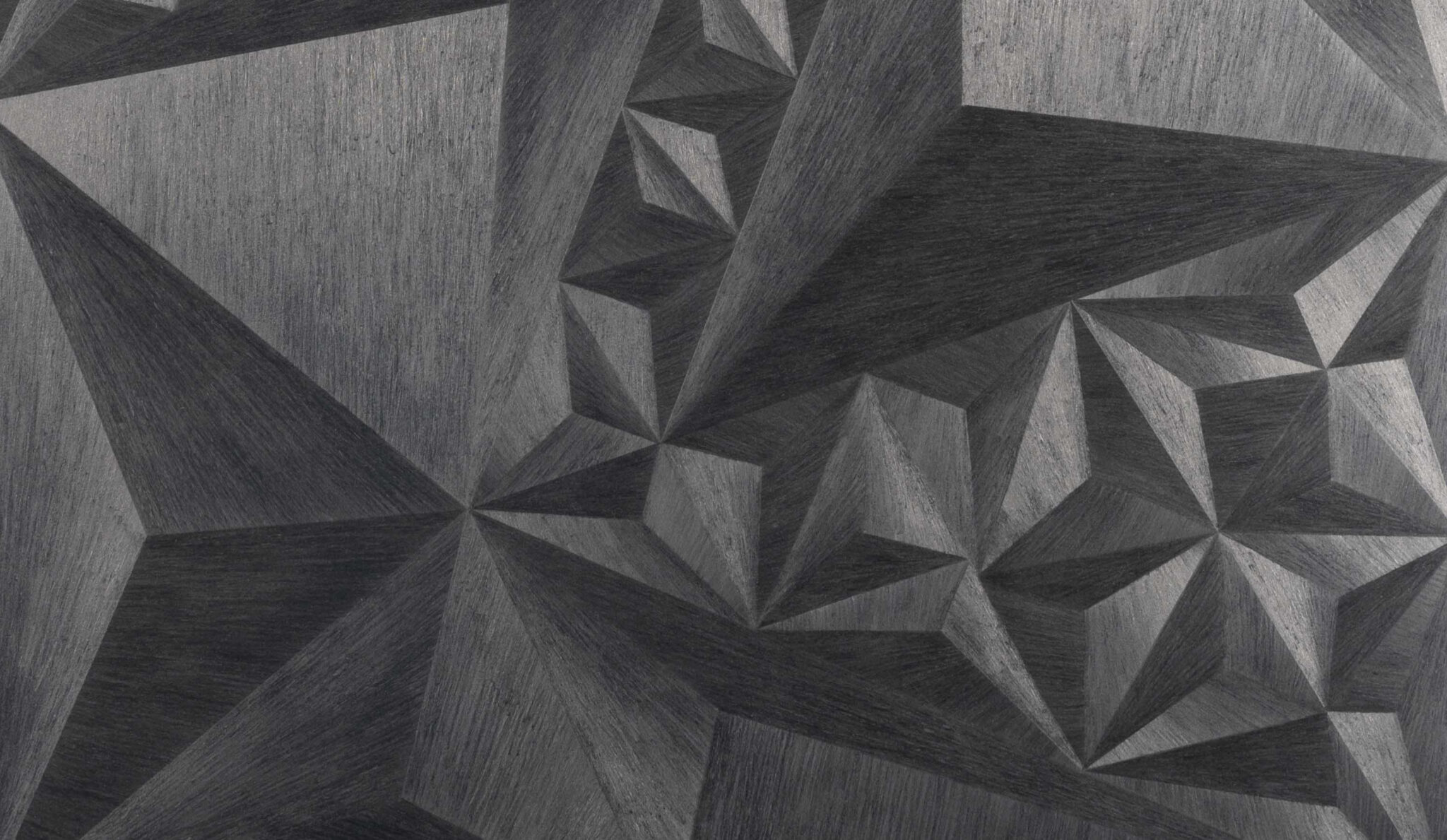

In the work of Julio Blancas (Gran Canaria, 1967), this current is rendered visible as a physical phenomenon. Not so much because it ‘represents’ a landscape, but because it evokes a state: that of being within an undated memory. There are artists who construct images. Blancas constructs a type of mental space: a place where sight is not limited to recognising shapes, but rather begins to remember without knowing what. What appears there is very particular: not a specific scene, but the feeling of having experienced something similar. As if the work were not in front of us, but all around.

There are forests that we enter through our eyes and leave through our hands. It’s not a friendly metaphor; it’s a bodily reaction. The body stands to attention or softens. The spine adjusts. The palms open, as if through that gesture they are trying to hold onto what they don’t understand. Sometimes our hands will fly up to our mouth, not out of fear, but out of disbelief: that ancient way of confirming that the surprise is real. That tremor – that silent ‘it can’t possibly be’ – is part of the work. Because there are images that are not meant to be looked at: they happen, as in Stoneway (2020).

And what happens here is similar to memory in its most stubborn form: appearance. A stone path in the middle of a forest can be a simple motif, a composition. But it can also be a key. The stones, repeated and uneven, somewhat resemble a personal archive: each one seems to hold a fragment of time. Not because they tell a story, but because they trigger a form of recognition that cannot be explained. It is too similar to us: the way we remember. Memory as ground. As a plot. Like something we step on without realising, and suddenly it forces us to stop.

That act of stopping is important. We are trained to overlook things: quickly, efficiently, productively. But to truly look— to stare, to look until something changes— is something else entirely. Staring is an act of concentration and, in a way, of nonconformity: it rejects distraction as the norm. Blancas’ work addresses that point. Each line insists. Each tone is constructed the way a thought is constructed when it is not abandoned halfway through. Here we won’t find the ‘idea’ of the forest but rather the time of the forest. Time deposited on the surface.

That’s why, when the motif shifts from the exterior to the hollow within—when the cave, the cavity within the rock appears— the symbolic becomes even clearer. A hollow is not an accident: it is an investment. The mountain is no longer defined by its elevation, but by its interior. It’s no longer a peak, it’s a dwelling. The gap, in terms of memory, is not absence: it is a place. A place where something is lodged. There are memories that are not clear images, but cavities: internal spaces that we return to without knowing why, with the certainty that inside there is something of ours, something that describes us like the openings in Tafonis (2020). Experience not as a postcard, but as a refuge.

Later came Phosphenes, a series from 2017: those images that appear in the darkness of the eye, when the body is stimulated and yet still sees. A phosphene is a flash without a world. And yet, it exists. It’s hard to think of a more accurate metaphor for certain memories: those that burst in without asking for permission, that light up a corner of the mind without bringing us a complete scene, just a glimmer. As if memory were also that: a stimulation. A crackling that sets the past in motion, not as a coherent narrative, but as a flash of lightning.

In that sense, Blancas’s work moves between two poles that need each other: the stone and the flash of light. The stone weighing down, enduring, insisting. The flash piercing through, appearing and disappearing, impossible to pin down. Between them, a form of experience is organised that is very close to ‘what happens while you live’: a combination of permanence and transience. Because living is just that: holding onto things and losing them at the same time. Learning to walk on shifting ground.

The stone, when presented as the central object, ceases to be a mere fragment of the landscape and becomes a sign. A personal kind of sign, pointing without explaining. Sometimes life behaves like that. It doesn’t offer you instructions; it offers you clues as does the piece entitled Stone (2021). And we must decide whether to take those signs to be warnings, reminders or obstacles. The stone can be a ‘broken step’ or it can be a ‘sign’: a point to pause, observe, work, concentrate. An invitation to look again. To look differently.

And that is perhaps the most silent lesson of all. Blancas not only shows; he alters the way we look. He shows us how to see things differently, not by lecturing, but through insistence. We agree to enter or leap into the image – Leap I (2025) – and, when we emerge, we are not the same. Because the eye has already become accustomed to density, to shadow, to patience. Because the body has already understood that an image can be a place and that a place can be a memory we didn’t know we had.

Ultimately, his work speaks of an impossibility: that of being outside the sphere of life’s action. No spectator is completely safe, completely distant. Looking is not a neutral act. Looking means allowing something to happen to you, inoculating yourself like Virus I (2019). And then the phrase becomes literal: ‘What happens while you live’ is what is happening to you now as you look. Not as a spectacle, but as an experience. Something moves inside: a reminiscence, a startling, a calmness. A hand that opens. A breath that alters.

Everything that Blancas seeks—without needing to declare it—inevitably comes to light in our own hours. Each piece acts as a parabolic mirror that does not reflect a face, but rather a time. And in that reflection there is a kind of luck: taking with you, forever, a foreign breath that is no longer foreign, because it has mixed with the fragile and powerful material of our memory.

_____________________________________

¹ Excerpt from the text by Carlos E. Pinto for study on Julio Blancas included in the BAC Library of Artists from the Canary Islands, published by the Government of the Canary Islands, where he describes the artist’s practice and commitment to his work.