Juan Ismael Art Center · Fuerteventura · Spain

6 JUL – 23 SEP. 2023

Casa de América · Madrid · Spain

11 OCT – 9 DEC. 2023

Curator_ OMAR-pascual castillo

Production_ Galería Artizar

DARKNESS WAS THE BEGINNING

Notes on a cosmogony from the work of Roberto Diago

Omar-Pascual Castillo

According to Ifá:

There is nothing finer

than one day after another

Yoruba proverb

1

The work of Cuban artist Roberto Diago (Havana, 1971) has gradually made him one of the most established and outstanding creators of his generation, both on his native island of Cuba and internationally. Over the course of more than three decades, he has progressively constructed an undeniable corpus precisely, among other reasons, because it is so forceful, embracing his subject matter head on with irrefutable success.

His art always evokes an embrace – in my view – because there is something in the constitution of his work, often grandiloquent, that appears to be created more by his arms than his hands, tending to stretch out in space like a spillage, bursting open, a slap around the eyes, rather than a caress, and this violence indicates the strength of the arm, rather than the delicacy of the hand. Even when the hand, detailed and precise as it is, when he wishes it to be, points the way to enter his universe.

2

That said, let us pause for a moment. I have not worked with Diago for more than twenty-five years, the fundamental reason being that I moved to Spain, and it has not been possible until today. As I have said many times, despite being considered from the outset a Cuban curator in Europe, always expected to offer Latin American art, when I arrived in Spain, our island home had fallen out of fashion. It had become over exposed; that was its fate, there’s no point in harping on about it. Hence, after so many years of not being able to approach his work, I am now obliged to make history. I am obliged to stress that we must observe his work as that of a black man, a native of Havana, descendant of the great painter of the Cuban historical avant-garde, Roberto Diago (his paternal grandfather) and of a family of musicians and music teachers, the Urfé family(1), kin to his paternal grandmother. In our native Cuba, he would be referred to as “a black man of some prestige, high born and highly educated”, but never milksop or a spoiled brat. The bearer of a legacy. The Crown Prince as he was jokingly nicknamed by his friends. Little did they know how much truth there was in that name.

Whether he likes it or not, Diago has an exceptional symbolic dowry. I don’t know of anyone else from my generation who can credibly offer as an autobiographical anecdote that as a child he used to draw with René Portocarrero, Raúl Milián and Mariano Rodríguez, and that drawing was one of his and his family’s “favourite forms of entertainment”. They preferred to give him a piece of paper and a crayola (the Cuban name for oil pastels) so that he would not go out and get himself killed in the street or play ball in every corner. And not many grew up seeing a sketch by Picasso, several by Lam, by Abela, or by Doña Amelia Peláez on the walls of their family home in Pogolotti. This is a fact that I remember, because I also led a privileged life when my mother was an editor at Letras Cubanas, and as a child I was lucky enough to meet the likes of Eliseo Diego, Cintio Vitier, Fina García Marruz and Dulce María Loynaz, among many others; and I told Diago this little anecdote when we met, and that complicity united us. The complicity of knowing that we are strangely fortunate because we were both born and raised in the outskirts of Havana, he in Marianao/Pogolotti, I in El Cerro, so we were also united by our humble beginnings. Supposedly cultured, but never precious.

JUAN ISMAEL ART CENTER GALLERIES. FUERTEVENTURA

3

Having said this, I must confess, while we are here, that approaching Roberto after a quarter of a century has meant observing his work almost as a tourist, as one who looks from outside and not only from outside the island, his natural habitat, where he still works and lives. An island that is sometimes spoken of very lightly because it is marked by very specific stereotypes, from a Western perspective and even from the academic perspective of certain lines of Cuban critical thinking that are racist in their deviatoric and disguised obstinacy; fundamentally due to ignorance because they do not know the ancestry of the Afro-Atlantic culture within which Diago moves. They have no idea of its burden.

Therefore, approaching his work today involves trying to rediscover Roberto Diago, an artist who caught my attention in the early 90s in Havana While the national context was pointing towards canonical representational aestheticism, what we commonly refer to as “Academic”, that supposed post-modern “new return to order” under the pretext of “restoring [an] aesthetic paradigm” that seemed to me to be a step backwards; Diago’s work was going against that grain.

Allow me to explain: while Agustín Bejarano, recently returned from a short period of exile in Brazil, was flooding our native Havana with large-scale paintings of “martyred guajiros” (stock peasant characters with the facial features of José Marti, our poet and national hero, a white man, by the way), and Arturo Montoto was delighting Havana officials with his tropical versions of postmodern Murillos or island Sánchez Cotánes – eminently imperial, aesthetically speaking, despite the neo-baroque costume-; both proposals were reactionary and backward, academic to the point of becoming scholastic, too paradigmatic and tremendously complacent. While the new graduates of the Higher Institute of Art (known as the ISA) swarmed around the ideas developed by the group of artists who participated in the exhibition Las Metáforas del Templo (The Metaphors of the Temple)(2); defined in terms of their artistic traits by the de-folklorisation of anthropological themes as a mark of national identity, which they claimed had been “abused” in the previous decade, along with their representational – academic – affiliation under the halo of neo-historicist painting or their more aseptic installation-based neo-conceptualism; Diago chose to buck this trend. And this voluntarism was endorsed by the understanding that, if it did indeed make sense to return to “a paradigm” of sorts, he already had his own, the one contributed by his legacy, approaching post-modernism not through rupture but from the perspective of “unfinished continuity”, that lingering after-taste within the modern, closer to the work of Lezama Lima than Lyotard; this earned my respect. I saw something there that refused to stop being what it was, “still asilvestrado” (feral), an Andalusian word that I love, even though I discovered it five years later. That primary, artisanal, rustic, persistent side truly captivated me.

4

The ironic thing is that these accusations often emanated from curators and academics of the first world, always willing to put Knowledge where the Other was obliged to put flavour.

Iván de la Nuez

Teoría de la Retaguardia

There are Cuban historians, critics and curators who did not see what happened in the early nineties as the whitewashing of our visual culture. There are those who do not perceive that ‘evil lurking in the background’, that belated triumph of the Bolshevik school that academised the provincial art schools with professors recently graduated from the Soviet Fine Arts Academies or from other former socialist countries of Eastern Europe; all branded with the seal of Socialist Realism. What they didn’t manage to do with music, they did with art. I don’t know why they can’t see it. Perhaps because they are not from Havana either, and that “new white guajirismo ” represented them then and still does today.

Sometimes, we just need to clean our lens a little, to remove the whitish dust of the whitewashing that the people of Cuba were subjected to over the past century. For example, no matter how well trained Diago has been in the Academy of San Alejandro, we cannot ask him not to be connected to the anthropocentric tradition of Cuban Art that he explores in the Afro-Atlantic legacies, initiated by the vertiginous and avant-garde work of Wifredo Lam, the mysterious painting of his paternal grandfather, Roberto Diago, and the voluminous sculptural fleshiness of Agustín Cárdenas in the early and middle twentieth century; because those foundations nourished him visually as a child. Therefore his attachment to the modern island tradition is natural; it comes from his cradle. And years later it is natural that he has communicated with the fabulist and mystical work of Manuel Mendive (whom Roberto admires and respects), with the neo-expressionist graphology of Eduardo Choco, and the anthropological research of José Bedia, María Magdalena Campos and Marta María Pérez Bravo into Afro-Atlantic cultures and creeds; with these precedents the artist enters Art through his racial condition as a Black man, city-dweller, urbanite, habanero, descendant of artists and musicians, as an individual transected by the transitory nature of the end of a century, where the diaspora is no longer an escape and takes a home, an outline, a familiarity as a starting point and an arrival point. As if the point itself, that black dot that’s not always perfect, rather than becoming a line, needed to be turned into a dot that travels in space, and this was his obsession. As if his training as a sculptor always pushed him to conceive all his work spatially, but his musical education opens out the perspective of his planimetries to emulate certain staves, certain organisational schemes, ruled by rhythm. Where brocading and burnishing, honouring the investigations of his paternal grandfather within graphics, reminded us of the evil doing of the last neo-expressionist painting of the twentieth century. Where the scratched mark, with feigned clumsiness, demonstrated dexterity, control, accuracy of gesture, indicating rebellion, disagreement, visual violence, grotesque seductive masking. Frontality, once again. A frontality that has remained in his work since then.

JUAN ISMAEL ART CENTER GALLERIES. FUERTEVENTURA

5

…in the case of the oppressed, the tradition of discontinuity demands a heroic will that eliminates the confirmation of past history. There is nothing grand or romantic about this heroism. Heroism is the willingness to take risks when confronted with power…

Bonaventura de Sousa Santos

Tesis sobre la decolonización de la historia

Cuban Art in recent decades has consistently shied away from referring to the social problems of raciality on the island because “it is not spoken about”; that which has supposedly been overcome structurally, not spoken about, is taboo. Even when we see that the Cuban political class is plagued by this process of whitewashing and machismo, better to leave it behind and continue towards the copyist stampede of trying to resemble what the West expects of us, being similar to what the West refers to as Art Today(3).

The curious thing is that Roberto’s clinging to his legacy, that militancy in the craft, the non-technological without being technophobic, saved him from passing trends and paved the way for him to become the successor to a very personal style of painting and the installation investigations that ushered in the second avant-garde, where the povera artistic vein takes on social dimensions previously silenced. It is not povera, it is poor, it is not symbolic, it is documentary.

Thus, what was initially a path of personal introspection, in which Diago gradually got to know himself, is now an expansive field in which the artist takes the time to turn his work into a machine of meaning. Flipping staid conceptualism and post-industrial minimalism, he rechristens the material as “something touched”, a “container of culture”, an “auratised thing” as a result of the path, part of the dilemma and focus of the issue.

We must remember that he graduated from the San Alejandro Academy of Sculpture, but sculpting is very expensive. Drawing less so, painting slightly more, but he managed to reuse truck tarps, packaging covers, jute, burlap and raw linen from sacks intended to transport food. At least when he first started out. He then made that scarcity his trademark, and poverty became the hallmark of his work, like a virus that infects everything it touches. Maybe because even if you are from a cultured, socialised, showy, dynamic family, if you live in Pogolotti, poverty surrounds you; you are caked in it, you reek of it, right down to the soles of your shoes. So when Diago speaks from there, he does not do so as a “rich kid, all grown up now”, but as an exceptional witness, as part of the problem. His cultural depth, his musical up-bringing, the Catholicism of his grandmother or the Afro-Cuban syncretism of his aunt, his family collection or his library (I remember his library with special envy); that baggage, that luxury, does not change his physiological traits on which centuries of social racism have been built around the world.

But like all of us from Havana, when he speaks of the city, when he diverts his attention from the subject to the predicate, to the urban landscape, he does not do so with nostalgia, nor is he dazzled by it the way that artists from provinces become fascinated with the capital and will do whatever it takes not to leave. Instead, he contemplates it through that dense love/hate relationship that we habaneros have with our city. He does so through disaster, debacle, decline and reconstruction. And there he connects with an artist that he may or may not know, the Algerian Kader Attia, who lives between Berlin, Barcelona and Paris. Kader has been talking about restoration for years, repairs that we must make to our Western culture if we want to heal colonial damage. He, as a man of northern African descent who lives in Europe, has that capacity. Like Diago, as a black man from Havana, he has that possibility to tell you about his race, from his dichotomous condition, culturally white, physically black. Closer to the approach of recycling turned into a system of resignification taken by El Anatsui or Ibrahim Mahama, than to the Puerto Rican Víctor Vázquez in his installations. Continuing along this digression of finding references and connections that my colleagues criticise me for -perhaps rightly so-, I see Diago increasingly as being more immediate to contemporary African artists than to Cuban and/or Caribbean artists who preceded or surround him; closer to Sammy Baloji, a Congolese artist recently exhibited in London’s Tate Modern, for whom the secret graphology that traces the scars on the skin of the original African peoples of his homeland marks the lines he embosses on metals and disembodies them, turning them into abstract landscapes, or as I have been saying lately, rather than abstracts that denote an ontological condition of being as a definition, abstracted, indicating temporality of a state; like Yaw Owusu, a Ghanaian artist who uses coins as the raw material in his work, playing with the idea of the “Value of Art” and the value of the metal that, when turned into currency, mutates into an “abstracted thing” juxtaposed over the bourgeois blank space, as if reminding observers that our national currencies are made of African metals.

6

That is why I am not surprised that he has chosen anthropological continuity as a support for his visual discourse, and I like to imagine that every time the artist articulates any word in his planimetries, he is silently saying a Moyugba: that sacred Yoruba prayer that calls out to the ancestors and to the Afro-Atlantic orishas and deities. He calls them, evokes them, invokes them. He asks for protection, help, a little faith still. When he weaves the textile braids that simulate a symbolic wound, he performs a break, a withdrawal and finally a Sarayeye. That cleansing, purifying ritual. Because of the use of such methods, we might think that he is socialising ritual, by making us, as the observing public, a historic ebbó. In fact, I even detect something of Capella Rothko, the famous installation of works by the great American abstract artist in the Menill Collection in Houston, in the montages of his monochrome paintings of wounds and marks made on black walls(4). I find something of that zen silence in these commissures, these scars healing, which remain there so that when we touch them, we recognise what we experience and who we are. I like to think that when he paints still lifes, he is making an addimu, that offering of flowers or fruits, which African ancestors and believers today make to our spirits and deities. Or that when he embosses the metals in his “fragments of history”, he implores Oggún to accompany him, to guide his hand, his arm, his torso, his heart. And so from the akokan, an ilé is made. From the heart, a home is made. Although for this he must build an immense Macuto from as much wood as he needs to build its walls, a refuge that shelters him.

In the year 1995, I ended a text I wrote about the artist with the following sentence: This… is THE WORK, the rest: is… pure ancestor, that is: CHAOS(5). Almost three decades later I would venture to say that the artist has learned to organise, control and manage that chaos in a masterful way. Despite the fact that this learning has come through unlearning. Retracing steps. Above all, when it expands into space, there is orderly chaos, propped-up disaster, sustained collapse. As if he is taxonomising the landscape that his eye catches in symbolic representations that avoid objectifying themselves as container spaces of beauty, because beauty isn’t there. To see this beauty, you must be able to live with this ugliness and see its useful side. Its condition of habitat, of habitable and inhabited place.

7

Note for fellow curators & co. Understanding the art produced by artists involved with or who have grown up amidst Caribbean syncretic rituality requires a more practical than theoretical methodological approach. If you have never seen a bembé you may never understand Mendive; if you have never been on a mat in front of a babalawo or olwo, you may not understand that Diago’s “magic cloths” are not wooden tongues, but mats, resized, although symbolically these mats know secret tongues; the artist starts from the idea of turning the fragile mat on which the religious undergo a dialogical consultation into a solid wall. Minimal, private, unipersonal almost, but flexible and solid enough to envelop us.

The fact that Diago does not develop work that delves into Afro-Cuban mythologies, as Mendive, Bedia, Ayón or Pérez Bravo do, does not mean that he does not know them(6); therefore, when approaching his work we should fit into our spyglass the respectful lens that the teacher Robert Farris Thompson used when referring to “primal cultures”, as he called them. If we add that lens of wisdom developed by the anthropologist and art historian, founder of the Yale Chair of African Studies, we will understand that Diago is not being influenced by his friend and colleague Belkis Ayon, when he silences the lips of his figures. Belkis did so in her excellent graphics because her work was about a secret creed, the Rule of Abbakúa, which literally translates as Secret Kimbisa Rule of Leopard Men; therefore, she was speaking of something that should not be spoken of; a secret. When Diago blots out the lips of his figures, he silences their story, their cries, their complaints, the rebellion of the Black man for centuries. Knowing that he is Yoruba, this is an open secret. And perhaps he is recalling with the stylisms of his figurations the drawings of his paternal grandfather or even Lam himself, rather than our beloved Belkis. Perhaps more inspired by the almond-shaped profiles of the bronze sculptures of the extinct Yoruba kingdom he saw on his first visit to Paris at the Museum of Man, than by any of his contemporaries. Something that does not separate them, but rather unites them. They are two sides of silencing. Two faces of our Afro-Cuban culture. The more faces the better, the more voices the better. And that is another syncretic trait that denotes his work, always adding, rarely subtracting. Adding baroque flourish to everything under an apparent flattening of the sense, towards a single resource: fire, patchwork, montage, weight, density, imprint, thrust.

As if in this process of constant restoration that is an evolution, a process of becoming, he wishes to restore the abandonment and the plunder to which his original people were subjected, giving them a place, a role, a history, a voice. As if striving to restore the failures of the modern Atlantic process. Heir to a legacy and bearer of a culture that floods him, Roberto is a creator who works with intensity and skill from various languages, drawing, painting, sculpture and installation. Reversing the scriptural logic of the “blank page”, knowing that in the beginning it is always in darkness where light is born, and not vice versa. Without fear of his own “blank page”, Roberto Diago has been writing our history, visually, re-writing that of his contemporaries, by sharing their work just like the metaphor used before, because he embraces us, just as the universe embraces this planet we call home.

JUAN ISMAEL ART CENTER GALLERIES. FUERTEVENTURA

8

To expose this ancestral, ecosystemic and contemporary “cosmogony” that Diago gives us is the curatorial goal of this exhibition to which this publication is a companion guide. This travelling exhibition(7) has been curated into three sections, based on his visions of “his people”, “his landscape”, “his home”. As the artist himself insists on looking for his place in the world. A place where he no longer has to paint with his grandfather’s brushes, not only because they were the only ones he had to hand, but because there were no others; rather because he now has his own; his own brushes and his own language, his own polyglot language, versed in Yoruba, in Spanish, in the slang of Havana and rural wisdom, European viola and Afro-Caribbean batá.

This is Diago’s first individual exhibition in a Spanish public institution, which will show around forty works including paintings, installations and sculptures, in which each space seeks to feel inhabited by its passers-by. Diago’s, and obviously, by us. His guests of honour.

If you know,

you know

Popular contemporary saying

Pepe Bedia and the Pinto family

who forced me to re-examine you

(1) We are talking about musicians, musicologists and cultural agents who stripped away all the foundations of the structure for spreading knowledge about Cuban musical culture, where folklore and popular culture played a fundamental role. His great-uncle Odilio Urfé was a musician, musicologist and ideologist of projects such as a register of Cuban folklore, festivals of Cuban folk and popular music, an institute of musicology, and several volumes of anthologies about danzón, son and other popular island music from the first half of the 20th century. He was a very important figure in the musical development of Cuba.

(2) Exhibition staged at the Centre for the Development of Visual Arts, Havana, Cuba, 1993-94.

(3) In this same line of work that links the Afro-Atlantic legacy as a living, resilient culture with contemporaneity is what the Keloides project (Part 1) proposed almost three decades ago, which we curated together with Alexis Esquivel in the Casa de África, an exhibition at which Diago was a guest artist. He was also invited by me as a curator in El ocultamiento de las almas (The Concealment of Souls), held at the Centre for the Development of Visual Arts, both exhibitions taking place in the year 1997. Later this curatorial path was further developed by Ariel Ribeaux (e.p.d.), Orlando Hernández and Alejandro de la Fuente, with exhibitions related to the subject such as Ni músico ni deportistas (Neither musician nor athlete), at the Provincial Centre of Plastic Arts and Design (Galería Luz y Oficio), Keloides, (Keloids) at the Centre for the Development of Visual Arts, from the year 1998 co-curated by Ribeaux and Esquivel, or more recently Sin máscaras/Without Masks curated by Orlando Hernández at the National Palace Museum of Fine Arts in Havana and the Johannesburg Gallery in South Africa, and Keloides III, which took place at the Wifredo Lam Centre and at Mattress Factory, Pittsburgh, curated by De la Fuente, in 2010.

(4) In this sense, his personal show El poder de tu alma (The Power of Your Soul) at the Wifredo Lam Centre, in Havana, in 2013/2014, curated by Jorge Fernández (director of the centre at that time), I think opened up that experience. Jorge and Maribel Acosta, the co-curator, spoke in their text of a hiatus in which Diago retains past and present, a perfect metaphor; an exhibition that personally seemed liminal to me and marked a turning point in the work of the artist.

(5) I am referring to the unpublished text PRIMERO FUE LA MATERIA, luego: EL CAOS Texto IN-material sobre la OBRA de Juan Roberto Diago-, from the book Palimpsestos Neo-Barrocos, winner of the AHS Writing Scholarship Award in the essay category, in Havana, Cuba, 1995.

(6) There is a mistaken, wholly erroneous popular perception that if a religious person, in any of the Cuban syncretic cults, is not “initiated”, this person is not as religious, and a wall of suspicion is raised, a certain distrust of the uninitiated, as if we were asking the alleyo (those who have taken the first right of initiation) to take a leap of faith constantly, crowning, scratching, initiating into Ifá, Abbakúa, PaloMonte or Ocha. And this error is rooted in the moment when the deities mark you or choose to adopt you, initiating you; this letter is only marked and signed when your body and your soul need it. So there are millions of believers of our creeds who do not need our deities to protect them, because they are the true elect, the new or too old souls who need no more light than they themselves have. Diago is one of them. For example. de ular io, Fuerteventura. preseradica, en nuestras deidades, eligen adoptarte a travnarte rto del Rosario, Fuerteventura. prese

(7) Opened in the summer of 2023, at the Juan Ismael Art Centre, in Puerto del Rosario, Fuerteventura. It will continue in Casa de América, Madrid, next autumn, with the invaluable involvement of Galería Artizar.

ROBERTO DIAGO Time’s witness

Suset Sánchez Sánchez

My final prayer: Oh my body, make of me a man who always questions.

Frantz Fanon.

The first dark shadow was cast by being wrenched from their everyday, familiar land, away from protecting gods and a tutelary community But that is nothing yet. Exile can be borne, even when it comes as a bolt from the blue. The second dark of night fell as tortures and the deterioration of person, the result of so many incredible Gehennas. Imagine two hundred human beings crammed into a space barely capable of containing a third of them. Imagine vomit, naked flesh, swarming lice, the dead slumped, the dying crouched. Imagine, if you can, the swirling red of mounting to the deck, the ramp they climbed, the black sun on the horizon, vertigo, this dizzying sky plastered to the waves. Over the course of more than two centuries, twenty, thirty million people deported. Worn down, in a debasement more eternal than apocalypse. But that is nothing yet.

Édouard Glissant

When we talk about the work of Diago (Juan Roberto Diago Durruthy, Havana, 1971), I always like to remember — maybe an occupational hazard as an historian, and not by way of an anecdote, but rather as an important fact that affirms the intellectual genealogy that precedes him — that he is the grandson of one of the most important figures of Cuba’s twentieth century avant-garde movement. The legacy of his grandfather, Juan Roberto Diago Querol (Havana, 1920 – Madrid, 1955), together with the pre-eminence of Wifredo Lam, constitutes one of the most significant notes in the island’s pictorial modernism; the home-grown variety, not the kind imported from Europe, in which Africa appeared only as a synthesis within formalistic expression. So the early Afro-descendant consciousness that awakened Diago’s imaginaries comes as no surprise, becoming political and ethno-racial agency that has taken him on a return transatlantic journey through which he emphatically explores the footprints of the African diaspora, revealing a Pan-Africanist drive for resistance that pierces the labyrinth of historical time and the violence of a silence imposed by the modern/colonial world system on the bodies and subjectivities of enslaved and racialised persons.

One of the ways discovered by Diago to weave such connections with his ancestors and the past is in the use of materials, usually raw canvas, recycled wood and metals, fragments of media that he fuses by means of montage and collage, making no attempt to disguise the traces left by this fusion in search of residual perfection, but rather leaving them in full view to metaphorise the scar, the keloids (the sign that represents the terror of the foreman’s whip on the backs of the Black slaves who worked the plantations). In that mark lies the symbol of the violence of colonial extractivism on an entire continent, of the rupture inflicted on communities, families and ways of life, and knowledge that had to be reconstructed from broken memories to reconfigure a different, syncretic and hybrid knowledge, from the otherness of subaltern voices against the white, male, western, bourgeois, heteropatriarchal, christian subject.

CASA DE AMERICA GALLERIES. MADRID

The artist stitches his fabrics and through that gesture seems to want to recompose those scattered memories. He uses this same procedure when soldering onto a metal surface, which translates back into a scar. Using these methods of assembly, his compositions are segmented into levels and geometric areas that inevitably penetrate the very history of modern art and abstraction to stress the different discursive axes that overlap in his works in the manner of a palimpsest. It is impossible when contemplating Diago’s works not to think about the process of whitewashing or bleaching carried out by European modernisms on material cultures and objects whose anthropological function was displaced by the exercise of an aesthetic synthesis of European isms that occurred in the first half of the century.

Diago’s aesthetic inquiry constantly swings between those false dualisms that the modern episteme tried to institute between “high-low” cultures, “abstraction-figuration”, “tradition-modernity”. For this artist, constructing the image becomes a tool that questions any type of canon seeking to impose itself on the free will of his exploration in the plural imaginaries that feed into his art and which encompass the History of Western art and the legends narrated by the griots when they arrived from the confines of the African continent to Afro-Latin America and in whose songs and stories the oral memory of different communities was kept alive. Thus, the very creation of his canvas medium plays with the illusory appearance of fragments, using small squares of fabric that are joined together in colour planes to configure the image. The smallest unit of the digital image, articulating the pixel, is cut here in a scrap or patch, reminiscent of those patchwork quilts sewn by our grandmothers in the evenings, when homes became a place of calm after the domestic maelstrom of the day. Thus, high and low technologies are transformed into a simulation game in Roberto Diago’s work, such as when he builds his photographic light boxes from old, recycled wooden pallets.

CASA DE AMERICA GALLERIES. MADRID

The use of recycling in Diago’s work is also a strategy of significance through which the artist refers to a historical and sociological practice of resistance among racialised subjects in the context of white and Creole cultural domination in Latin America and the Caribbean. The operations of transculturation conceptualised by anthropologist Fernando Ortiz around 1940 in his seminal book Contrapunteo cubano del tabaco y el azúcar serve as a foundation to explain the use that subaltern subjectivities make of materials appropriate to the dominant culture, which are resignified through practices of syncretism, hybridisation and camouflage. A classic example in this sense is the emulation of the Catholic saints in the gods of the Yoruba pantheon, a process of transvestitism through which religious practices and rituals of African descent could endure in the colonial territory.

When, in a piece such as Resistiendo en el tiempo (Resisting in time, 2017), Diago reuses metal sheets from industrial production and assembles them to build a geometric block whose imposing volume refers to a modern sculptural school that began in early twentieth century Europe and recalls the forceful forms of postwar American minimalism or the inventions of the Italian povera movement, he holds the registers of modern art in tension with a geopolitical modernity that was forged in the first modernity described by Enrique Dussel in the emergence of the world system:

Modernity, as a new “paradigm” of daily life, of understanding history, science, and religion, emerged at the end of the 15th century with the dominance of the Atlantic. The 17th century is the product of the 16th century; Holland, France, England, are subsequent development in the horizon opened by Portugal and Spain. Latin America enters Modernity (long before North America) as the “other side” dominated, exploited, concealed.(1)

That apparently aseptic sculpture, with perfect geometry barely corroded by the rust smelling of saltpetre, resulting from the location of the hunk of metal in the Malecón seawall of Havana, facing the sea that flows into the Atlantic, with the military fortresses built between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries to defend the colonial enterprise standing as time’s witnesses, seems to reject a late modernist artistic genealogy to inscribe itself in the centre of the history of the modern / colonial world system, which is also the history of slavery in Afro-Latin America. This iron figure that simulates a shipping container returns us to a time of violence when the transatlantic journey defined the trafficking of Black bodies, transported as commodities in the triangular system of the slave trade between Africa, Latin America and Europe. But at the same time, it places us in a global trans-historical time where the subordinate subjects of the past experience new forms of oppression under the renewed dynamics of slavery entailed by emigration in a post-colonial world in which the inequalities established by the structural racism of modernity endure.

Similarly, the artist’s work using recycled wood to create large-scale installations from polychromatic boards harks back to the original image of the slave ship in the tragic epic of slavery, which becomes a kind of womb for enslaved bodies, giving birth to a new culture made from the shreds of the transplanted memory of the African diaspora. Sometimes these collages of assembled sticks take the form of improvised and precarious constructions, overcrowded dwellings that stretch up to the sky like the favela slums of the Brazilian hills (Historia Permanente II [Permanent History], 2020). On other occasions, the accumulation of wooden crates winds along the vertical axis, sketching out a kind of Tower of Babel that takes us back to that cultural origin of the slave ship in the transnational construction of the Caribbean, incubated in the heterogeneity and consequent creolisation (Edouard Glissant) of the different ethnicities and languages that were overcrowded and carried in the bellies of the slave ships (Ciudad quemada II [Burned City II], 2017).

…First, the time you fell into the belly of the boat. For, in your poetic vision, a boat has no belly; a boat does not swallow up, does not devour; a boat is steered by open skies. Yet, the belly of this boat dissolves you, precipitates you into a non-world from which you cry out. This boat is a womb, a womb abyss. It generates the clamour of your protests; it also produces all the coming unanimity. Although you are alone in this suffering, you share in the unknown with others whom you have yet to know. This boat is your womb, a matrix, and yet it expels you. This boat: pregnant with as many dead as living under sentence of death.(2)

It is in this wooden cavern, genesis of the deferred knowledge of the African diaspora, symbolised in the room of fragments, that the artist composes, like a great mural of neo-concretist inspiration, the series El rostro de la verdad (The Face of Truth, 2013), where the subject matter claims prime place of enunciation within a hierarchy of discourse that has repeatedly excluded the Afro-descendant polyphony of languages and ethno-racial agencies.

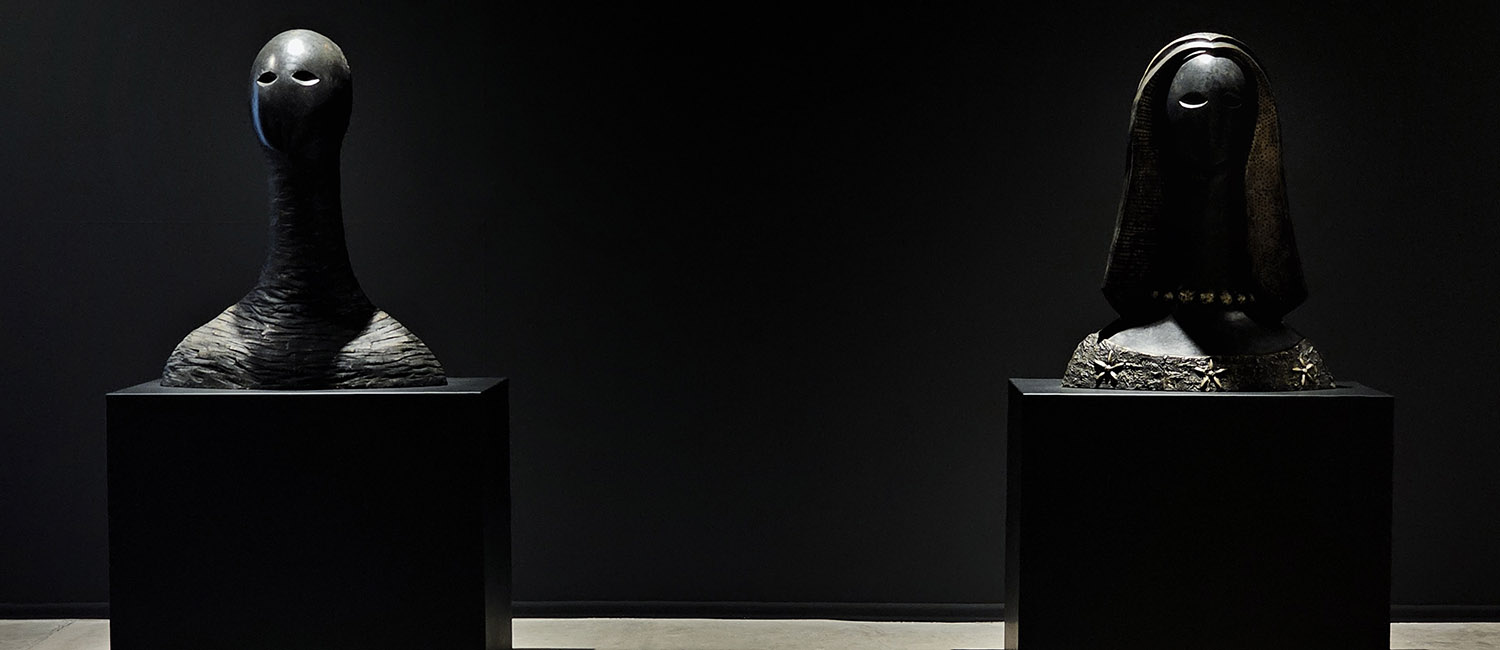

A symbolic effigy embodies that witness of time in Diago’s work, a character we might assume is some kind of self-representation of the artist at times and with whom the artist identifies, as he has stated in various interviews. It is that schematic black silhouette, where the almond-shaped eyes like cowries or snail shells are related to Eleguá (the Orisha that opens the way in the belief system known as Regla de Osha-Ifá). This figure observes us from the depth of these cavities bored into the face like eye sockets; but he does not speak. He has historically been deprived of a voice that was sequestered along with the richness of his original cultures. Black voices that were marginalised, excluded, silenced, and expelled from the order of discourse.

In this exhibition, Diago brings that recognisable sign of his canvases to a three-dimensional sculptural concept and also makes a foray into the use of bronze as a material. Once again, his use of artistic material forces us to think of another sequestration, for example that of the Benin Bronzes, which are still exhibited in Western museums as a testimony to colonialist usurpation.

CASA DE AMERICA GALLERIES. MADRID

The artist still dares to recover the significant power of wood as a material that connotes the time of colonial violence. Diago recreates these same enigmatic mutated silhouettes in the series of assembled wooden sculptures Libertad (Freedom, 2022) and Hombres Libres (Freed Men, 2022). Once again, recycled and repurposed material points to a disruptive zone between the geopolitics of Western colonialist history and the history of modern art. The stylisation and aestheticisation of the objectual and ritual culture of different African ethnic groups in the fetishism of sculpture and modernist painting of the first European avant-gardes of the twentieth century, is called into question in these busts in which wood is transformed into skin and gives body to beings whose silent hieratism stands as an emblem of dignity, stoicism and Black pride.

However, it is perhaps that latent voice, which remains indomitable in the memory of the African diaspora, that is replicated in each of the pieces and fragments of wood in that great sculpture-tongue, which resembles a mat like the ones often found in the sacred rooms where the priests of Ifá or Babalawos carry out the divinatory process of Ifá. In that place, and on a fibrous mat, the messages of Orula, Orisha of knowledge, are interpreted through the gift of divination. There, the ancestors and the dead are invoked, and the Yoruba language resonates once more with all its decolonial power. It is in the modern daily practice of traditions of African descent that the Black body ceases to be a silent witness to colonial genocide; his voice emerges as a cry that pierces the deaf labyrinth of historical time to declare the strength of Afro-descendant political agencies that neither slavery nor racism have been able to subjugate.

(1) Enrique Dussel, “Europa, modernidad y eurocentrismo”, in Edgardo Lander (ed.), La colonialidad del saber: eurocentrismo y ciencias sociales. Perspectivas latinoamericanas. Buenos Aires: CLACSO, 2000, p. 48.

(2) Édouard Glissant, Poética de la relación. Bernal: Universidad Nacional de Quilmes, 2017, p. 40.

TV PROGRAMME METRÓPOLIS (RTVE) DEDICATED TO ROBERTO DIAGO AND THE EXHIBITION LA OSCURIDAD FUE EL PRINCIPIO (DARKNESS WAS THE BEGINNING)

Production_

Centro de Arte Juan Ismael

Galería Artizar

Editorial concept_

Omar-Pascual Castillo

Texts_

Rito Ramón Aroche

Janet Batet

Omar-Pascual Castillo

Bárbaro Martínez-Ruiz

Suset Sánchez Sánchez

Translations_

Anna Moorby

Design and layout_

Pepa Parrilla

Impression_

Anel Gráfica Ediciones

Binding_

Ramos

Photography_

Galería Artizar

Francesco Allegretto

Mellissa Blackall

Fundación Clément

Roberto Chile

Carlos de Saá

Alain Gutiérrez

Rodolfo Martínez

Marcos Harold Linares García

Juan Carlos Romero

Roberto Diago Studio_

Mayrene Zaldívar García (assistant)

Yaima González Álvarez (assistant)

Agustín Hernández Carlos (assistant)

Marcos Harold Linares García

(assistant and photographer)